Everyone seems to have an opinion on the paleo approach to eating, and often it’s a strong one. From anthropologists to acclaimed authors, nutritionists to naturopaths, Crossfit trainers to colonic hydrotherapists, and pretty much any health-conscious individual in between – the paleo movement now seems less like a fad and more like a dietary era in itself.

What is it?

Also known as the "caveman diet", "Stone Age diet", and "hunter-gatherer diet", it is a diet centred on fish, grass-fed pasture raised meats, eggs, vegetables, fruit, fungi, roots, and nuts.

It has many different interpretations but generally excludes grains, legumes, dairy products, refined salt, refined sugar, and processed oils – basically any foods perceived to be agricultural products. Stricter variations of the diet exclude some or all fruits.

Generally it is a high fat, moderate protein and low to moderate carbohydrate wholefood-based way of eating with the intention of granting long term health, resilience, and well-being.

Like most “diets” or ways of eating, there are many different interpretations, and there is both good and bad to come out of it. Unlike many fads, there is scientific evidence supporting some of the Paleo diet claims. But how solid is the evidence, and what are the long term pros and cons of the Paleo diet? To answer these questions from a balanced perspective, we need to dive a little deeper.

Where did it come from?

Throughout the eighties, numerous books were published about diets based on achieving the same proportions of nutrients (fat, protein, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals) as were present in the diets of late Paleolithic people.

Some very influential scientists have conducted population studies on traditional peoples who do not suffer from diseases of modernity such as diabetes, hypertension, ischaemic heart disease, or stroke. Weston A Price, Thomas Cleave and Staffan Lindeberg were pioneers in pointing out that certain foods in a modern Western diet which would not have been available during early human evolution cause serious health problems.

The foods at fault included refined flour, sugar, and modern processed vegetable fats.

Based on the early work of these wholefood grand-daddies, and a growing mountain of evidence of varying quality, paleo proponents argue that modern human populations subsisting on traditional diets (allegedly similar to those of Paleolithic hunter-gatherers), are largely free of diseases of affluence such as cardiovascular disease, cancer and diabetes, and that Paleolithic diets in humans have shown improved health outcomes relative to other widely-recommended diets.

Fast forward to the year 2010 and beyond, and everyone from anthropologists to Crossfit trainers seems to have their own opinion on the paleo diet. A number of medical doctors and nutritionists advocate a return to such a diet, with countless books and websites created to promote varying paleo dietary prescriptions.

Which Paleo diet?

Some paleo-pros are very exacting about the proportions of fat, protein and carbohydrates in the diet. Some followers allow starchy vegetables such as sweet potatoes, whilst others strictly forbid them. Still other paleo enthusiasts allow fruit whilst others shun it altogether for its high fructose (sugar) content. Some take the middle path and allow small amounts of low sugar fruit such as berries.

For the sake of simplicity, let’s take a commonly accepted version of paleolithic eating that I’m seeing more of. The growing number of Paleo restaurants that have sprung up around the country seem to take a somewhat flexible interpretation. I recently visited The Paleo Café, the newest addition to the sprawling selection of eateries in Burleigh Heads, on the sunny Gold Coast.

Their menu takes this more widely adopted interpretation of the Paleo diet, and includes sweet potato, seeds, and some fruit whilst still avoiding dairy, grains, legumes, added sugars and preservatives “which our bodies were not designed to digest” according to the café’s flyers.

Whilst researching this article I enjoyed a delicious salmon and roast vegetable salad in the sun and sipped on a berry and banana smoothie. Fellow diners enjoyed free range omelettes and meaty dishes peppered with greens and colourful vegetables.

The Pros

That’s quite an extensive list!

Anecdotal evidence aside, from a purely nutritional point of view I believe the Paleo diet deserves a big tick for its emphasis on whole foods in their raw, unrefined state.

PROS:

- Eliminates reliance on white refined carbohydrates

- Encourages lots of vegetables

- Discourages processed snack foods, which are high in calories yet low in nutrients

- Paleo diets are naturally low in refined sugar

- Weight loss may occur because fewer calories are being eaten, and “empty calories” have been eliminated. Keep in mind that for most people who embark on weight loss dieting, weight loss is usually temporary (2-5 years maximum) - even if health markers do improve - and comes with attendant physical and psychological risks.

Most nutritionists agree that the Paleo diet gets at least one thing right: cutting down on processed foods that have been highly modified from their original wholefood state through various methods of processing. Mo more white bread and other refined flour products, artificial cheese, certain cold cuts and packaged meats, potato chips, and sugary cereals. Such processed foods often offer fewer nutrients than their unprocessed equivalents, and some are packed with sodium and preservatives that may increase the risk of heart disease and certain cancers.

Paleo diets recommend against the highly-processed foods - rich in added sugar, trans fats and salt - that characterise the modern Western diet. For this they deserve a big bowl of credit. But some nutritionists argue that the paleo diet ignores the benefits of many plant-based foods (including fruit, nuts, whole grains and legumes) and some dairy products, such as traditionally prepared organic yoghurt and kefir.

Paleo & Weight Loss

paleo diet manipulates quantities of protein, fats and carbohydrates and most diets that do this

will work in the short term because their inevitable restrictions cut energy intake.

Protein seems to take front row while carbohydrate is shoved to the cramped seat in the back. This in itself can become a major problem with the paleo diet.

Having recently attended an intensive training in nutritional and environmental medicine, I came face to face with some of the biggest fans and most convincing advocates of the Paleo movement: doctors with an interest in integrative medicine. Armed with some of the newest science, I had some fascinating discussions with doctors who excitedly told me that they now “knew what breakfast to recommend to their diabetic patients – bacon and eggs.”

Can I just say, from a nutritional perspective (let alone a mental health one): this is NOT a great life-long recommendation.

Protein was the word of the day. Sitting next to doctors piling their plates with meat at the beautiful wholefood lunches and hearing such recommendations quite frankly put me (a dietitian with a working knowledge of the benefits of a plant-based diet and the risks of a high animal protein, low carbohydrate diet) into a mild state of panic.

Crossfit exercisers are some of the hugest drivers of the Paleo approach to eating I’ve spoken with. These wonderfully fit people rarely fail to point out their increased need for protein due to their intense training.

Yet the very reason some of them come to see me in clinic is because despite their incredibly clean diets and active lifestyles, they are utterly exhausted, their hormones are totally out of whack, and their sugar cravings are overwhelming.

This is the point at which a Paleo diet has been interpreted as a high animal-protein, low- carbohydrate diet i.e. it becomes something reminiscent of Atkins (remember that dark age?)

And for Crossfit enthusiasts or any athlete doing intense training up to three times a day, not getting enough carbohydrate – the primary fuel our bodies use for energy - is a perfect recipe for fatigue and accelerated ageing.

Even for non-athletes and the average person trying to lose weight, ultra-restrictive versions of the paleo diet - those cutting out all complex carbohydrates and sugars - just don’t last. People on calorie restricted diets centred on meat and low-carbohydrate veggies may lose weight initially, but the sugar cravings, fatigue and boredom lead to inevitable weight re-gain and keep them coming back to the next diet.

Risks of too much animal protein

Any excess protein you are not using isn't stored by the body as protein; it is converted to fat or eliminated via the kidneys in urine. Eliminating excess nitrogen this way leaches calcium and other precious minerals from the bones and can create kidney stones.

Vegetable foods are generally alkaline, whilst animal products are acidic (1). When you eat a meal high in animal protein such as a big steak, the food is digested with the help of a significant surge of hydrochloric acid from the stomach. The broken down steak is then absorbed into the bloodstream where it significantly raises the acid tide in the blood. This requires an equally strong alkaline response by the body to buffer the acid, because your body always likes to maintain your blood at a slightly alkaline pH – this way our tissues remain well oxygenated. We get the needed alkaline buffer from our bones, which give up their phosphates and calcium - minerals our bones need to stay strong.

Over time a high animal protein diet excessively dissolves minerals from bones and stimulates bone turnover which can lead to osteoporosis, osteoarthritis and calcium deposits in other tissues (1,2).

It's all in the interpretation

But that doesn’t mean that a no-grain or a low-carbohydrate diet is safe, sensible or sustainable.

As curious and opinionated humans we tend to polarise and meddle in extremes, despite our advocating moderation. It seems inevitable that some people will always interpret the available science and take on the more extreme interpretation of the paleo diet, when really people just want an excuse to eat more meat.

But I don’t blame them - our taste buds are naturally drawn to high nutrient foods such as meat, salt and sugar, because the presence of these in a wholefood generally means it's also packed with antioxidants, vitamins, minerals and other nutrients.

It’s an evolutionary survival adaptation that unfortunately lands us in trouble in our modern world of convenient, processed and factory-farmed food. Piling one’s plate with meat and throwing in a salad is a tendency that I’m seeing with increasing frequency, all in the name of "honouring our genetic code".

However, it's difficult to conclude that modern humans should mainly eat meat, with a few vegetables thrown in. Early humans had diverse diets, depending on where and when they lived, and archaeologists are finding ever more evidence that even our earliest ancestors ate more grains than we once thought.

The cons

And the "2 million years of evidence can't be wrong" argument is too sweeping an assumption to me. It assumes that there is only one paleo diet and that it was eaten consistently by peoples worldwide, when in actual fact there were hundreds of paleolithic diets dependent on season, locale, and other shifting cultural factors.

Cons of the Paleo diet:

- Very little science backing up some of the Paleo Diet claims

- No large studies assessing Paleo Diet for long-term weight loss and maintenance

- Ultra-restrictive versions of Paleo don’t last

- Too hard to maintain over a long period of time, which leads to yo-yo dieting and can

- mean poorer health

- Beans and whole grains, which are not allowed, are an important source of nutrients

- and fiber (3), plus an eco-friendly source of protein

- Large reliance on meat, which has repeatedly been shown to increase risk of disease

- and can be very taxing on the environment depending on methods of animal husbandry used

- Many paleo eaters rely heavily on coconut products, which are imported from far

- away and thus carry a huge carbon footprint

- Can be time consuming and expensive

- Processed meats and a weekly intake of more than 450 grams of red meat (including

- pork) increase the risk of colorectal cancer (4)

- Negative impact on gut flora (5).

Basic assumptions of Paleo Eating

- That human genetics have barely changed since the dawn of agriculture, which marked the end of the Paleolithic era, around 15 000 years ago

- That modern humans are adapted to the diets of the Paleolithic period, and

- That it is even possible for modern science to discern exactly what such diets consisted of.

These foundations have been challenged by a number of scientists. Evolutionary biologist Marlene Zuk has written a book titled Paleofantasy in which she debunks many myths about the Paleo diet. She argues that we are not biologically identical to our Paleolithic predecessors, nor do we have access to the foods they ate.

Just about every fruit, vegetable or animal species commonly consumed today is drastically different from its Paleolithic predecessor. Even if domesticated animals are grass-fed, their flesh is unlike that of wild animals - kangaroo being the exception. Free-range poultry don’t just forage but are fed grains, unlike wild birds. Wild-caught fish are an option, but there are simply not enough of them to go around.

Even if we look to modern foraging societies to deduce paleo-like dietary guidelines, the variation in geography, season and opportunity between different traditional cultures makes this difficult.

There is even evidence suggesting that our paleolithic ancestors weren’t the sculpted Adonises immune to all disease that we assume they were. Our ancestors often had brief life spans, and new evidence suggests they also suffered from so-called modern lifestyle diseases.

Signs of atherosclerosis - arteries clogged with cholesterol and fats – have been found in more than one hundred ancient mummies from societies of farmers, foragers and hunter-gatherers around the world (6,7).

Is it nutritionally sound?

So let’s come back to the nutritional side of things.

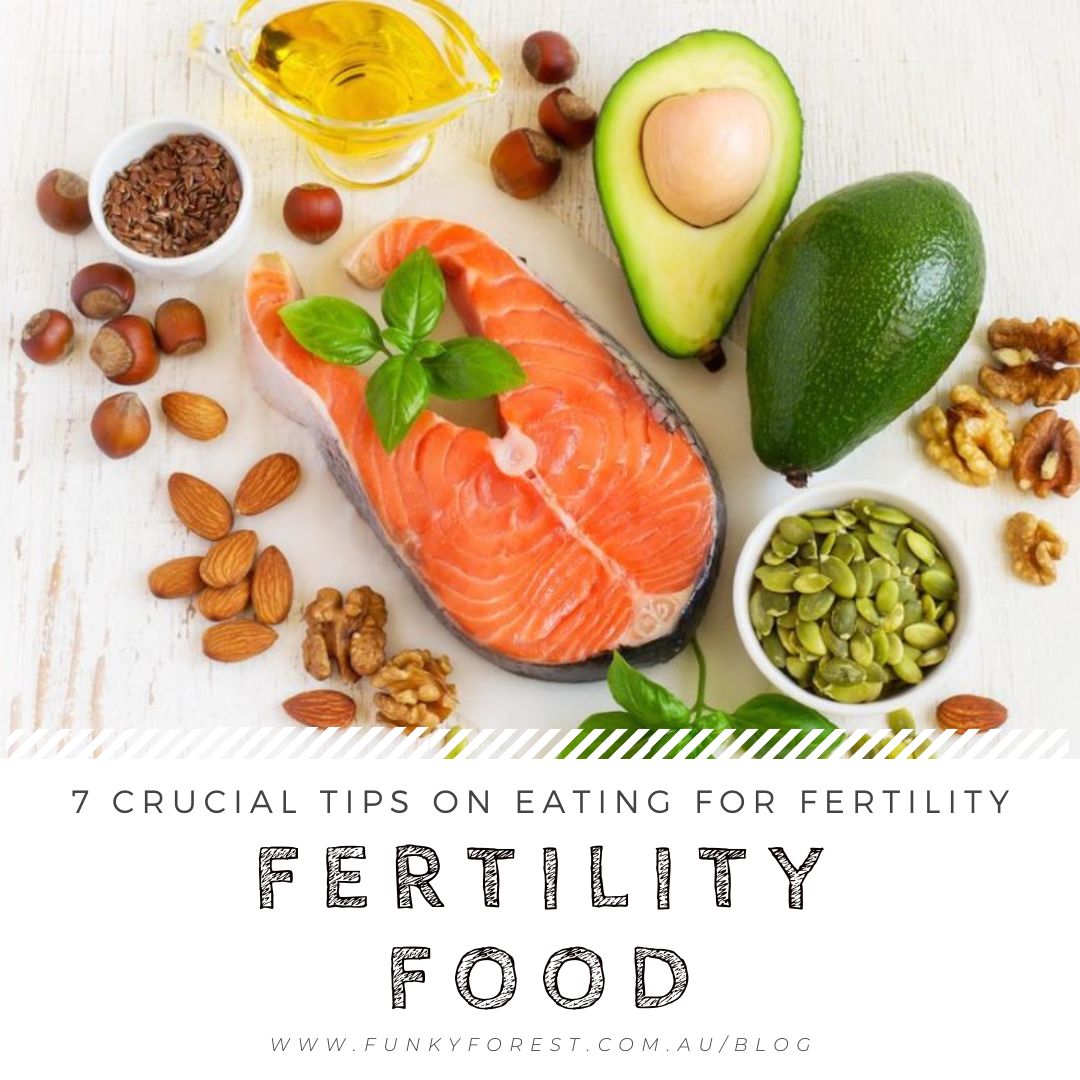

As a holistic dietitian I feel that the principles of the less extreme versions of the “paleo diet” (and remember that is basically the branding of it) are sound: eat lots of vegetables, include healthy protein such as some lean meats, some nuts, fruit and eggs, reduce processed sugar, refined carbohydrates, trans fats, and modernised dairy.

Where things go awry is in the practical application of the diet, especially when it’s taken to the extreme. It’s wonderful to see people cutting down on processed foods, but the obsession that some paleo enthusiasts have with eating grass fed animal protein two to three times a day is not good for anyone, least of all the environment.

I’m no anthropologist but I have trouble with the idea that paleolithic people ate meat several times a day, most days. Animals are hard to catch, especially with paleolithic technology.

For contemporary cultures that live traditionally with old technology, for example African tribal and nomadic peoples, game meat is important, but not a three-times daily, every day event due to the effort involved in catching it.

Where meat is more commonly eaten it's usually due to herding, which is not a paleolithic but a neolithic practice.

In truth, there is evidence for whichever side of the argument you decide to take, including the exact opposite to the Paleo approach – the high carbohydrate, low animal protein, plant- based approach. The work of Colin Campbell and Cardwell Esselstyn exemplifies the many benefits of such a diet. These guys emphasise the importance of including grains and legumes as part of a balanced diet, based on the evidence that the intake of wholegrain foods protects against heart disease and stroke. The fibre, magnesium, folate and vitamins B6 and vitamin E from whole grains may be important reasons behind these health benefits. Consumption of a few serves of whole grain and/or high fibre foods per day is associated with reduced risk of weight gain, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and colorectal cancer (3).

Recommendations

But for an athlete, or even for the recreationally active that need a little carbohydrate, a hard-core paleo diet often ends up in poorer diet quality when the sugar cravings hit, in my clinical experience. The pull of sugar is just too strong. Downing a pack of tim tams is not healthier than eating a little rice.

If you want to go paleo, I recommend you stick to the basic premises of the diet and practice balance and moderation. Eat lots of fresh vegetables, fresh game meat and minimise processed food where possible, making sure you don't become rigid and disordered about this (which is an inherent risk in any dietary dogma) and turn a couple of healthy-sounding suggestions into another version of The Wellness Diet.

Fuel your body with complex wholefood based carbohydrates such as starchy vegetables and some ancient grains, especially if you’re exercising. And eat according to appetite.

But what I suggest even more is to practice intuitive eating. Don’t just rely on the clinical evidence – it’s about as mixed as a meat and potato stew. Similarly, don’t depend on testimonials alone - these vary from, “I lost 30kg and kept it off on paleo,” to, “I became severely constipated on paleo and my sugar cravings were through the roof.” We need to get some answers from inside ourselves.

What feels good for YOU? Not what your Crossfit friend says or your vegan activist friend suggests. If the idea appeals to you, which parts of it appeal? Paleo is not a singular entity but a very mixed bag of widely varying options depending on the “expert” you are talking to.

Maybe a few eggs a week feels good for you, but having them every day for breakfast with steak for lunch and dinner doesn’t sit right.

Use a balance of nutritional common sense and intuition. If you’re living in a city working in a sedentary office job, and eating meat three times a day doesn’t feel intuitively right to you, it probably isn’t. But if you’re an inuit, it probably will.

The paleo movement gets a big tick for its push towards real foods. We should be eating real foods. That means foods that we grow, hunt or pick. Foods that are unmodified and come from nature. When possible, we should aim for the most nutrient dense foods, because that’s why we eat, to nourish!

Not to accomplish some idealised pre-agricultural macronutrient ratio.

Article by Casey Conroy originally published in Living Now magazine, 2015.

References

- Sellmeyer DE, Stone KL, Sebastian A, Cummings SR (2001). A high ratio of dietary animal to vegetable protein increases the rate of bone loss and the risk of fracture in postmenopausal women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 73, pp 118-122.

- Feskanich D, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA (1996). Protein consumption and bone fractures in women. American Journal of Epidemiology. 143, pp 472-479.

- Flight I; Clifton P (2006). Cereal grains and legumes in the prevention of coronary heart disease and stroke: a review of the literature. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 60, pp 1145–1159.

- Bastide NM, Pierre FH, Corpet DE (2011). Heme Iron from Meat and Risk of Colorectal Cancer: A Meta-analysis and a Review of the Mechanisms Involved. Cancer Prevention Research. 4, p 177.

- Scott KP, Gratz SW, Sheridan PO, Flint HJ, Duncan SH (2013). The influence of diet on the gut microbiota. Pharmacological Research. 69:1, pp 52-60.

- Hill K, Hurtado AM, Walker RS (2007). High adult mortality among Hiwi hunter-gatherers: Implications for human evolution. Journal of Human Evolution. 52:4, pp 443-454.

- Thompson RC et al, (2013). Atherosclerosis across 4000 years of human history: the Horus study of four ancient populations. Lancet. 381, pp 1211-1222.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed